The Reverend Madeleine Urion is rector of St. George’s in the Diocese of Edmonton, and a signatory to the ACCtoo open letter. She believes that honest dialogue is necessary for people and institutions to begin healing, and that honest dialogue begins with recognizing where transformation is needed.

Content Warning: This article discusses spiritual abuse and sexual violence as perpetrated by church leaders, including within the Indian Residential School system.

Six days before the Passover Jesus came to Bethany, the home of Lazarus, whom he had raised from the dead. There they gave a dinner for him. Martha served, and Lazarus was one of those at the table with him. Mary took a pound of costly perfume made of pure nard, anointed Jesus’ feet, and wiped them with her hair. The house was filled with the fragrance of the perfume. But Judas Iscariot, one of his disciples (the one who was about to betray him), said, “Why was this perfume not sold for three hundred denarii and the money given to the poor?” (He said this not because he cared about the poor, but because he was a thief; he kept the common purse and used to steal what was put into it.) Jesus said, “Leave her alone. She bought it so that she might keep it for the day of my burial. You always have the poor with you, but you do not always have me” (John 12:1-8).

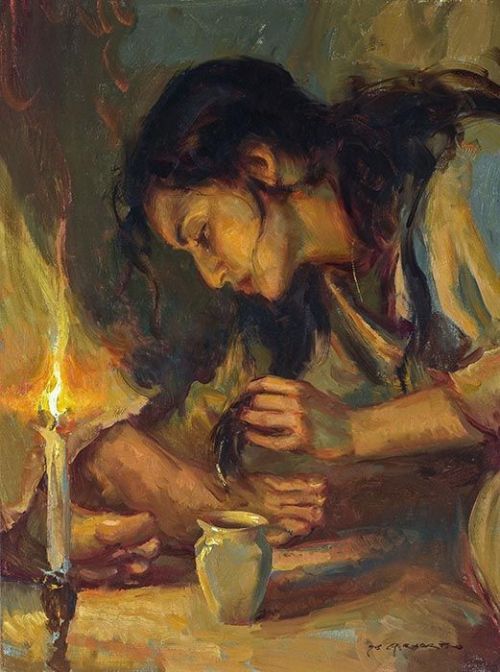

Mary sits on the floor, with her head covering unfurled. Her hair is clumping together in oily strands, full of the potent, heady aroma of the nard she scoops out of the jar and rubs into the feet of her friend. It’s a scene that might evoke familiar reactions from any who have known the truth and have felt that they’ve had no other option than to tell their truth despite the cost. She’s the sole woman in that room, seemingly powerless on the floor while the disciples look on and Judas shifts with discomfort at what looks to him like a dramatic, overly emotional display of affection.

How do Judas and Jesus each respond to Mary?

For those in the room, it would have been shocking to see a woman—unapologetic in her womanhood, in her sexuality, and in her grief—boldly enter the room where Jesus is with his disciples, remove her head covering without shame or explanation, and purposefully express her love for Jesus and for the liberation she experiences in his presence. Judas’ response is to shut it down at all costs, to shame her, to spin the situation for his own ends. “Leave her alone,” Jesus says. “She bought it for the day of my burial. You always have the poor with you, but you do not always have me.” Mary’s testimony matters to Jesus, and in Mark’s Gospel he says even more about Mary’s actions: “Truly I tell you, wherever the good news is proclaimed in the whole world, what she has done will be told in remembrance of her” (Mark 14:3-9).

But do Mary and her testimony matter to us? Are we remembering her?

As I sit with this passage, I cannot help but recognize the truth it speaks into our own moment in time. So many of us are reeling and trying to find our centre of gravity in our vocations, lay and ordained, as we are confronted with the truth again and again that people within the institution we love and that we have striven to serve have abused, ignored, groomed, and exploited those who are most vulnerable. We know about this happening in a colonial context in this land, with clergy and staff of residential schools systematically neglecting, spiritually abusing, and sexually exploiting Indigenous children who were forcibly removed from their homes and families. That is a deep, more complex, and horrifying sin than I have words to describe here. We have only begun to reckon with this history, and many among us are recognizing that our vocation as faith leaders has become one of refusing to look away from the horror of the past and the way this past has created systemic injustice in the present. We are learning that we must practice holding the horror of our history in tension with our hope in the redeeming power and love of Christ in our present and our future. We are learning that holding hope in the redeeming power of Christ means submitting to Christ with a repentant spirit as we earnestly seek and welcome tangible ways to participate in acts of reconciliation today. This will be lifelong work, and it demands relentless faithfulness to the gospel and the prayerful submission of our conscience to the Spirit “who helps us in our weakness” (Romans 8:26).

We are also learning that abuse within the church isn’t limited to history. Recently we have heard of new allegations of sexual abuse committed by leaders in our church—by people trusted to lead congregations—and how survivors have been treated in their efforts to seek justice and prevent perpetrators from harming others. The #ACCtoo movement seeks to bring light to this treatment, exposing how the church has handled allegations with disregard of the humanity and safety of the survivors involved. The truth, sadly, seems evident: when the sexual sin of those among us casts a shadow upon the body of Christ, the urge is to control the story and minimize the elements that are most damaging to the institution.

How do we respond to survivors?

Unless we truly listen to those who are telling us they are hurting, all we are doing is further participating in their dehumanization—the same kind of dehumanization Judas offered to Mary. When Jesus tells Judas to leave Mary alone, I must wonder if he is offering us instruction that fits seamlessly into the rest of the Good News that he brings: when someone is telling us that he or she is hurting, we are morally obligated to listen to them. To park our own personal reactions to our own fears of what they are saying and to listen deeply, quietly, and generously. As followers of Jesus, and for those among us who have taken vows to this end, we are especially obligated to listen when they are telling us they have been hurt by the church. We are especially obligated to witness to their humanity, to their unequivocal belovedness to the Lord of Life whom we love, and to assure them that their stories are handled with care and respect. That Jesus —whose human experience is coloured as much by interactions with broken institutions as broken people—desires no one to be collateral damage out of a misguided urge to preserve any institution.

We must fearlessly examine our place as a church in this mess.

How can it be that there is a cost to telling the truth in an institution that is built upon the truth of the Good News of Jesus, in which we attend services perfumed with the same heady moments of incense? Why are we shifting the focus away from people who have told us that they are hurting to questions of policy and procedure? Why, when are consecrated to live out the truth that “in serving the helpless [we are] serving Christ himself” (BAS p.655), and we pray for the anointing of the Spirit to this end, do we think altering policies will rectify this situation? Yes, policy and procedure must change, but our first call is to be the Body of Christ. This is first and foremost a matter of conscience, not policy. Do we pray to be united to Jesus in his sacrifice, and then balk when we fear what that requires of us? No amount of procedural change will truly bring healing or transformation unless the hearts and minds of those who draft and abide by these policies are aligned with our most fundamental call as the Body of Christ: to “repent, for the kingdom of heaven is near.” We cannot, in good faith, “seek to transform unjust structures of society” (the fourth of our Five Marks of Mission) beyond our own household when it has become abundantly clear that this mission must first be to our own selves. Portraying these failures as emerging primarily from a lack of adequate policy or procedure or from misinformed leadership appears as a managing of expectations to justify our own ends. It does not truly embody Christlike love or faith. It is sinful, and we must acknowledge this truth if we take our baptismal and ordination vows seriously.

Six days after Mary entered the room and anointed Jesus’ feet with perfume and tears, Jesus stood before Pilate and said, “For this I was born, and for this I came into the world, to testify to the truth. Everyone who belongs to the truth listens to my voice.” (John 18:37) Pilate asks him, “What is truth?”

When we fail to elevate the humanity of the hurting over the stability of an “institution,” even when that institution is full of people pure of heart, we dismiss the fullness of the truth. In doing so we hijack the mission of the church with our fears and failures, and we create the conditions for the church to, in effect, consume itself. And when we shift our focus to changes of policy and procedure rather than our own capacity to incarnate the Good News of what repentance offers, we become an obstacle for God’s mission in the world.

How are we to respond to Mary—and to whatever she has to tell us?

We are to welcome her story in the way she chooses to tell it. We are to assure her that she is heard and that her personhood is far more precious to God than a policy or procedure, no matter how well developed or informed it is or how many others it has kept safe. We are to tell her that her testimony matters. We are to admit our failures to protect one another from the unchecked and unwanted desires of those who have exploited their leadership and hurt others. We are to take some responsibility for ourselves and repent as we have been commanded to do.

Many among us are crying out for true metanoia. We long to be part of a church that takes its mission in the world so seriously that it is willing to die to itself and be transformed. We long to truly become what we pray for and to be united to Christ in his sacrifice, and trust that when Jesus said “repent, for the kingdom of heaven is near,” he meant it. We are lamenting that, by all outward appearances, we take this command more seriously than some in our highest leadership.

Genuine repentance is an acknowledgement that we have failed. Yet more than this, it is the gateway to truly incarnating the Spirit that dwells in our hearts through our baptisms. When we have taken holy orders, we further commit ourselves to leading and caring for the church in ways that require us to unite ourselves to Christ and to teach Christ’s saving and healing grace. These orders require us to be prostrate before Jesus in our leadership, joining Mary in her grief and in her courage and boldly calling out the times that we have dehumanized one another for the sake of a false and temporary sense of safety. We are not called to hover over a situation, to manage the optics quietly, or to do damage control on an issue of our own making.

Without true repentance we create the conditions for our own demise. Jesus invites us to become united with him in his sacrifice. May we, in this moment of reckoning with the truth, behold our call to teach and incarnate the truth that “one who would be great among us must be the servant of all.”